“Chess is a fairy tale of 1,001 blunders.”

—SAVIELLY TARTAKOWER

The vivid characters of Duchamp's Pipe include Marcel's friends from his early life in Paris—the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire (above right), the flamboyant Dadaist artist Francis Picabia (above left) and the writer Gabrielle Buffet Picabia (center). In 1912, Duchamp, Apollinaire and Francis Picabia took a perilous nighttime car trip on the Jura-Paris road to retrieve Gabrielle Buffet. The journey affected Duchamp deeply - his poetic notes on it appear in his collection of work The Green Box (1934). Apollinaire transformed his memories of the treacherous trip into an ominous vision of World War I in his poem The Little Car (1916).

Our characters in this story are the ironic Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), the witty, resilient Belgian chess champion George Koltanowski (1903–2000) and the game of chess itself. The two men knew each other for forty years through the overlapping circles of the international chess world—crossing paths in tournaments in Brussels, Paris and then, following World War II, in New York, where they created lively ventures involving art and chess. They played with brilliant chess masters, musicians, artists and writers.

Marcel Duchamp

George Koltanowski

As individuals, they had similar and contradictory traits: George, the mathematically gifted son of Polish Jewish immigrants to Antwerp in Belgium, and Marcel, the artistic son of an established cultured French family in Normandy.

From the age of eleven, Duchamp played chess with his older brothers in their cultured family home.

Koltanowski learned chess in his teens by watching his father and brothers play chess, later becoming the world blindfold champion of chess - a game that he played by ear rather than with his eyes. In 1937 he broke the Guinness Book of Records with his Edinburgh triumph of thirty-four matches played simultaneously.

But that was before World War II scattered the bohemians of Europe across the globe.

From Marcel Duchamp's arrival in New York in 1915, he played at grandmaster Frank Marshall's Chess Divan, later known as Marshall's Chess Club. Koltanowski also did displays there in the late 1930s. Above, George Koltanowski at the left in Barcelona in 1935, Frank Marshall, center, 1920s, and on the right, Marcel Duchamp at the Hamburg Chess Tournament, 1931, where he played Frank Marshall to a draw.

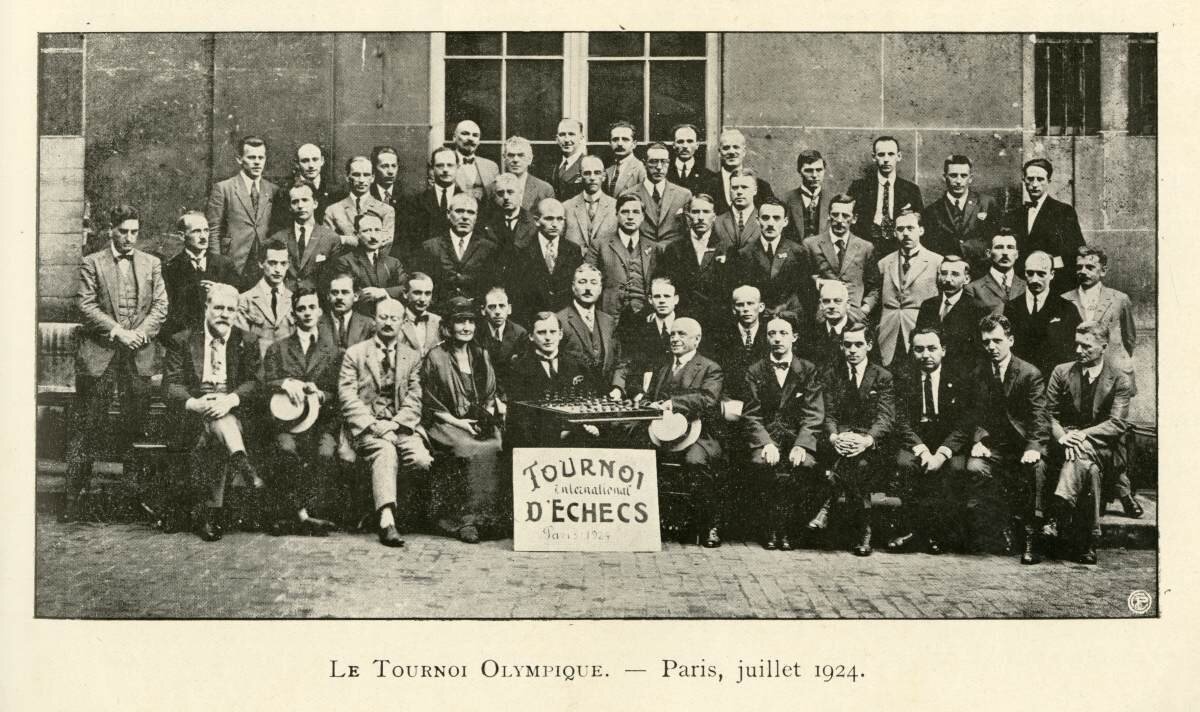

Duchamp and Koltanowski first met in Ghent in June 1923, playing on opposing chess clubs - George for the Cercle Maccabi and Duchamp for Le Cygne. They met again when they played in the first unofficial Chess Olympiad of the FIDE (International Chess Federation) in Paris in 1924. They are pictured above in a photograph of the winners in that Olympiad - Marcel at the top right, and George third from the left in the second row. They continued to play throughout the 1920s and 1930s, connecting at matches in the Hague and elsewhere. And they both became chess writers.

But this is only the beginning of the story of Duchamp's Pipe.

Once he arrived in North America, Koltanowski expanded the audience for chess. A showman, he fascinated large audiences with his astonishing displays of memory in the medieval chess game of the Knight's Tour. Koltanowski moved from New York to Santa Rosa, California and then to San Francisco in 1947. Making his new home in California, he became the chess columnist for the Santa Rosa Press Democrat in 1947 and the San Francisco Chronicle in 1948 - salting witticisms and anecdotes into his 52-year chess column.

“A game of chess is a visual and plastic thing, and if it isn't geometric in the static sense of the word, it is mechanical, since it moves. It's a drawing; it's a mechanical reality.”

—MARCEL DUCHAMP

Marcel Duchamp by George de Zayas, 1919.

George Koltanowski by T Camacho, 1939.

Although Duchamp returned to France in 1947 and 1950, he never again lived there full-time, and he took out American citizenship in 1955. He continued his art and chess playing in New York, fascinating many younger artists. At Duchamp's 1965 exhibition Hommage à Caissa (Homage to Chess) in New York, Andy Warhol filmed Duchamp playing chess with his old friend - and secret associate -Salvador Dali.

“Celia Rabinovitch gives us a first-rate art historical detective story—a page-turner that is hard to put down. . We are riveted by the story of the blindfolded chess player, and a detailed history of Duchamp’s life in the chess world. She is one of the most brilliant and intuitive thinkers on Surrealism. Duchamp’s Pipe is a marvel of scholarship and a delight!”

-—ANN McCOY, artist, art critic, and editor at the Brooklyn Rail